In 2010, I began recording Buddhist texts to listen to and reflect on. Among these was the first chapter of The Perfection of Wisdom in Eight Thousand Lines, and the Verses on the Perfection of Wisdom…

Since I was living in the city, and working, I needed to record these late at night, and edit them on my days off. I was inspired by reading even this much of the text, and I started to think of recording the entire sutra, but I realized I’d need to get away from the city to take on a project of that size.

In 2012, I had the good fortune to go on an extended retreat, in the mountains of Washington State, and one of my aims while there was to record and edit this wonderful book. The Perfection of Wisdom in Eight Thousand Lines, it should be said, is a spiritual classic, and one of the root texts of Mahayana Buddhism.

By the Fall of that year, as the days grew shorter, I’d completed the recording, and over the Winter months, in my little cabin, I set myself to editing it.

Here is the finished version, The Perfection of Wisdom in Eight Thousand Lines.

Recording Sutras

In general, to record a sutra, or any deep text, a person needs to understand it, at least to some extent, so he can read with a feeling for what the words express. Reflecting on this sutra, then, became one of my main activities that year on retreat. Together with quiet meditation, and metta (loving kindness practice) my time away was both enjoyable and fulfilling.

The Middle Way teachings opened the door to the Prajna Paramita

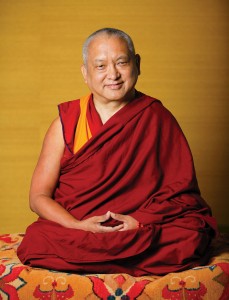

The year before heading North, I found Lama Zopa Rinpoche’s Light on the Path teachings online, and focussed in on his wisdom teachings from those retreats. I edited the audio, and produced a transcript that brought together his Madhyamika or Middle Way teachings, that illuminate the nature of the ignorance that is the cause of suffering.

There he taught extensively on the verse

Like a star, a visual aberration, a flame of a lamp,

An illusion, a drop of dew, or a bubble,

A dream, a flash of lightning, a cloud –

See conditioned things as such!

Studying these teachings intensively opened the door for me to understand more deeply the Perfection of Wisdom Sutras.

Historically, the Perfection of Wisdom Sutras followed after the Buddha’s teachings on no-self, or an-atman, and the Middle Way came after them, correcting some of the mistakes people were making, in misinterpreting what had come down to them. The Madhymika teaches freedom from the two extremes, of nihilism, neglecting cause and effect, and what they call ‘eternalism’, fixating on things as they appear to common, untrained minds. They explicitly identify the false appearance to the mind as ‘the object to be refuted’ (the ‘gak-cha’)This helps us to understand exactly what is negated, no more and no less, and to see the earlier Buddhist Wisdom teachings in their true light.

(‘This is a perfection of what is not’, says the Prajna Paramita)

Surprise and delight

Approaching these Buddhist wisdom teachings, I was expecting deep philosophy, which of course is there in abundance. What was an unexpected surprise and delight was to find just how much of a devotional quality this text has. There are praises, and expositions on its great value running through this sacred document.

I was also moved to see how the Perfection of Wisdom Sutras are pervaded by compassion. There is great bodhisattva poetry throughout. Here is where we find that renowned texts such as the Heart Sutra, and the Diamond Sutra are actually rooted in the loving Mahayana Ideal, of freeing all beings from suffering. If we take these texts removed from their source, we may miss this vital point, but it is clear as can be in the Eight Thousand Line Perfection of Wisdom. Although Wisdom is its principal theme, the Method side of the Path is fully represented.

Themes

The two main themes of this work are liberating insight, and, how that can be carried forward into our lives and work helping others.

If people do not exist as they, or we, commonly believe, then how are we to think of them, and interact with them?

This question is asked in many ways throughout the sutra. For example,

…when the notion of suffering

and beings leads him to think:

‘Suffering I shall remove,

the weal of the world I shall work!’

Beings are then imagined,

a self is imagined,

the practice of wisdom,

the highest perfection, is lacking.

and

dharmas do not exist

in such a way as foolish, untaught,

common people

are accustomed to suppose.

How then do they exist?

The Diamond Sutra presents this same challenge:

…we must lead all these beings to the ultimate nirvana so that they can be liberated. And when this innumerable, immeasurable, infinite number of beings has become liberated, we do not, in truth, think that a single being has been liberated,’

“Why is this so? If, Subhuti, a bodhisattva holds on to the idea that a self, a person, a living being, or a life span exists, that person is not an authentic bodhisattva.”

Here it is answered in various, creative, insightful ways, such as:

The skill in means of a Bodhisattva

consists in this,

that he cognizes that sign,

both its mark and cause,

and yet he surrenders himself

completely to the Signless [realm of dharma,

in which no sign has ever arisen].

and,

‘one treats an actually non-existent objective support as a sign,

as an objective support.

The act of will (of a bodhisattva, in truth, actually) arises only in reference

to the conventional expressions current in the world.’

Integrating insight

The insight that is gained through deep practice is different from intellectual understanding alone, and it has to be fully integrated into our lives and interactions.

In Buddhism, the cause of human suffering is a self grasping ignorance that is habitual and pervasive. When this is seen through, or seen for what it is, we experience ourselves and others and our world differently. Grasping at a self unconsciously cuts us off from our ancestors, our teachers, from one another and from our natural world.Removing this false view, we awaken to our connectedness, and inner treasures, joy, compassion, and peace. We enter into a dynamic, creative involvement with all our family and world.

Ego grasping is not an intellectual problem – the need for samadhi

If all it took to correct our view was to have it explained to us once, then it would be over in ten minutes. But we have lifetimes of habits of thought and action that need to be transformed through deep practice and sustained insight.

Buddhist lay practitioners in particular are prone to undervalue samadhi, or deep and clear, extended meditation practice, especially since it is difficult to cultivate in our modern world, and in our spare time. Ultimately we can see for ourselves if our way of practicing is effective at freeing us from suffering. The traditional teachings say that wisdom is like the sharp, precise edge of an ax, and that the strength of our meditation practice is like the powerful arm that wields the handle. If either element, the strength or precision is lacking, it’s difficult or impossible to cut through illusion.

Tibetan teachings also have a series of images they use to illustrate progress in meditation. They begin with a black elephant that gradually turns white as we transform the mind and our experience. As long as the wisdom of no self (or realizing that things lack independent existence) is in one place, and our life is in another, then we need more retreat time and thorough, transformative practice.

The Utility of Synonyms

The word ‘emptiness’ appears more than eighty times in the Perfection of Wisdom in Eight Thousand Lines, but so do many other terms for the same insight or way of understanding our experience.

They speak, for example, of

the absence of own-being in beings,

of

not coursing in a sign

The absence of imaginings

about any dharma whatsoever

the track of non-production

the non-appropriation of all dharmas

‘Not grasping at any dharma’ by name,

non-attachment to all dharmas

and more.

This is useful so that we don’t attach to any one way of thinking, especially if a key term, such as ‘empty’, can be confused with its more common meanings. The meaning in this context is brought out fully in the Sutra by expressing the same idea in so many ways.

From ‘Ah’ to One Hundred Thousand Lines

It’s natural to ask, if the meaning of the Prajna Paramita Sutras can be expressed in 14 Lines (The Heart Sutra), or 300 Lines (The Diamond Sutra), or even with the single syllable, Ah, then what is the need for the longer sutras?

The purpose of repeating or rephrasing a theme is to give us time to dwell on it deeply, or see it from another point of view. Attentively reading or reciting or listening to a long sutra can be an extended form of meditation, so that what we hear can inform our life and practice. Then when we hear or read the more concise texts, such as the Heart Sutra, it is a fuller, and deeper experience.

Selections

I know how a larger sutra may seem daunting for someone coming to it for the first time. With that in mind, I’ve selected one hour of the reading, to serve as an introduction. People can listen to this, or read the words and see if it appeals to them.

Reformatting the text

As much as I admire Dr. Conze’s translation, one problem I had with this text as it has been published is with the formatting. There are sections that go on for pages without a period, or a paragraph break. This makes it very difficult to read, or to recite. I can imagine how this would put some people off, which would be a pity. The book is formatted in prose, but for ease of reading and recitation, I’ve put all of it in verse format, here.

For 2,000 years, the Perfection of Wisdom Sutras have been passed down as among the world’s great religious treasures. In them we find all the elements of Mahayana Buddhist Philosophy. They are a source of world-nourishing rivers.

It is my hope that this Great Sutra in particular will be more widely known and appreciated, as it shows us how we can liberate ourselves, and places right in the palm of our hand the means of profoundly helping others.

May the Dharma be read and heard by all who can benefit from it;

May people be inspired to study and practice,

and bring forth the flower of their own wisdom and compassion.

May we all receive the teachings that enable us to do this.

Profound work, a dependent arising, a conceptual designation and yet it appears nicely to the mind.

Thank you again Jason