In the Fall of 2013, I started what I thought was going to be a simple project that would take me a few months: I was going to organize my father’s photographs. I had no idea at the time how this would lead me into a deeper relationship with the man who was my hero, and role model in many ways…

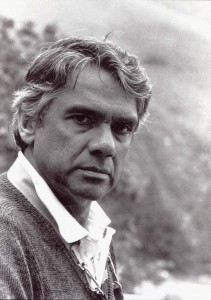

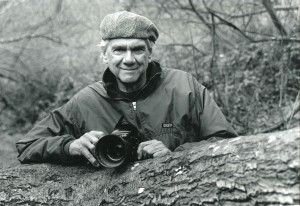

Big Sur, California, 1984, photograph by Jason Espada

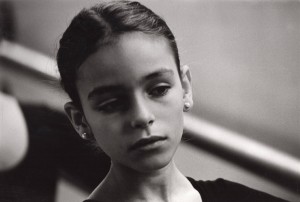

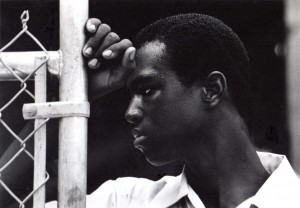

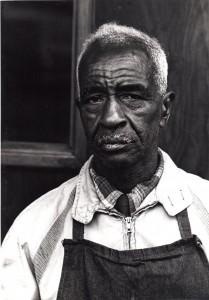

I wanted to help my parents sell some of my father’s fine work, as they often struggled to make ends meet, but we didn’t know what we had, or where it was. The method my father had used to identify photographs was very much like him. He called the prints by their names, and we got to be familiar with quite a few: The Ballerina, Paloma, The Man by the Fence, Margarite, Confessor, Jaime Jenkins, Willie Collozo, and others. This works well with maybe a few dozen photographs, but it doesn’t work when you want to have a comprehensive record.

{All photographs by Frank Espada, except where noted}

My father’s photography was produced over 60 years, and for reasons that I could see played out time and again, the prints from different projects were all mixed together- like shuffled decks of cards, I would say. When I helped my parents move out of their home in San Francisco, part of that labor was packing their photographs, and as I tried to get my father to help me determine what print went where, he’d pick one up and look at it, and get this far off look in his eyes. He’d last about fifteen or twenty minutes before saying, ‘that’s it’ and going upstairs. I ended up madly tossing everything into boxes and sealing them up, maybe to be sorted at some future time, or maybe not.

I had this sudden flash back in 2012 that what we needed was a visual record of what they had. I even started photographing his photographs with a card in front of the first print in a box, but then I let that drop and went off for a year. When I came back to California, I picked up where I left off. It took a bit of forethought to figure out a system that would account for more than two thousand prints, but I finally figured out that by using a large format scanner, I could scan 95% of his work, and assign a box letter and number to each print. Then I could print out a catalogue with thumbnails and we could see what we had, and where everything was. Sounds easy, right?

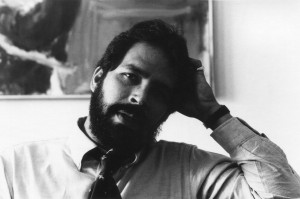

Photograph by David Haberstich

I finally convinced my parents to let me start scanning them. At first my father resisted – he didn’t understand what I had in mind, but after a couple of months I was able to show him what they looked like on his computer, and that I could print out contact sheets, box by box. It looked like we were getting somewhere. We had even begun identifying our favorite photographs, to be taken around to galleries. The fun part was within sight, at last.

On February 14th, 2014, my father had a major heart attack. I was with him in the hospital that night, and the next day, and he passed away on Sunday, the 16th. I think he knew he wasn’t going to make it out of the hospital that time. Quietly, he said he would’t be able to make our meeting to choose the photographs together with my mother and I, like we had planned. And so another chapter began, one I didn’t see coming at all.

I always had this image in my mind that grieving was something a person had time to do, in quiet, solitary moments. Little did I know that after a person passes away, it’s something you do when you can find a sliver of time. There is so much to attend to, not the least of which is caring for and comforting others in the family.

We needed to move my mother from their place in Pacifica, to an apartment, and find a way to store the archive. I asked a family friend, Karen Ande, what the best outcome could be for an artist’s work, and she said, the ideal would be for it to all land in one place, where it could be seen and appreciated in times to come.

Karen on Teresita Willie Vazquez

By that point, I had almost finished scanning the vintage prints, around 2000 of them. I’d been communicating with gallery owners, universities, and collectors. It was discouraging for a while until a family friend, Willie Vasquez, told me that the Smithsonian had a Latino Center, and that he had been in touch with someone there, and had given him my father’s book on The Puerto Rican Diaspora. I spoke with Ranald Woodaman, who told me the general impression in the museum world was that Duke University had gotten most of my father’s work. When I told him that, no, actually what they had was less than twenty percent of it, he was surprised and delighted. He sent out a message to curators across the Smithsonian network, and several of them responded, expressing interest in visiting to see the collection.

In 2014, we had visits from curators from the Urban Studies Museum, the American Art Museum, and the American History Museum. The National Portrait Gallery and the American Art Museum each acquired a select number of prints, and in June of 2016, the American History Museum welcomed into their permanent collection Frank Espada’s Puerto Rican Diaspora Documentary Project. This includes over 140 recorded interviews from across the country, all made between 1979 to 1981. I couldn’t be happier about this. It means that artists and activists, students and educators in this and coming generations will have access to his inspiring work.

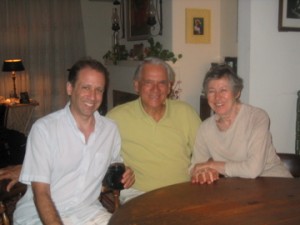

Smithsonian curator Steve Velasquez and myself, photographs by David Haberstich

This is the story so far, that anyone can see. There is a public record of it. What I’d like to tell now is how this whole process changed me.

My father’s first student

When we had the memorial for my father in March of 2014, people turned up that we hadn’t seen in some cases in twenty years. These were his students, and they remembered my father and his teaching like no time had passed at all. He had that kind of an impact on people. A few remarked that they were his earliest students out here, something they were proud to say. After a while though, I remembered something I hadn’t thought about much before, and that is, that I was my father’s first student.

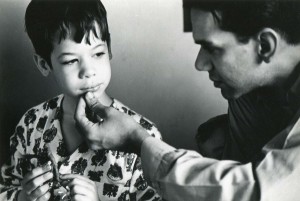

In 1970, we moved from Brooklyn to Valley Stream, Long Island, and in the basement of that house was a large cedar fur closet, that my father transformed into the first darkroom he ever had. Up until that time, handling his Nikon was a challenge for a young boy like me. If there are pictures taken of my father, they were likely done by my mother, who got to be pretty good at it herself.

Martin and Frank, photograph by Marilyn Espada

By the time I was ten years old though, I started taking photographs, and I remember the first time we went into the darkroom. It was beautiful in there: red safelights, trays all lined up, an impressive enlarger, and most of all, I was with the master, my father. We projected an image onto the light sensitive paper, and he had me take it to the developer tray, and move it around by the edge with rubber tipped tongs. What happened next is something I’ll never forget. Slowly, the image began appearing on the paper. I can still feel my father standing behind me, and smiling at my wonder. He was very wise about not saying anything, but just letting me see for myself what this was all about. This is probably why I remember it like it was yesterday.

I lasted as his student for about five years. Around the time I was fifteen, I discovered music, girls, and partying, all at once, and so I set photography to one side. We always had this language we could share, though.

India, 1998, photographs by Jason Espada

I remember years before, learning to use a black cloth bag to roll our own film, and how to put exposed film onto spools to be developed, going by touch alone. I also saw how meticulous he could be when it came to his system, which was very much his own. The chemistry, the temperature of the solution and water used, the timing, right down to the number of times to shake the film canister – all this was engrained knowledge for him, and written down for it’s own sake. Maybe some day in the future others could learn from it.

He also taught me, and later his other students how to ‘push’ film – that is, to expose it at a different rate than its marketed setting (pushing ASA 400 to 1200, for example), and to develop it in a unique way to get the best possible negative. There are a lot of ways of working with a poor negative, I learned, but, he told me, if you have an excellent negative, most of the work of making a good print is already done.

When I stepped back from taking pictures and got more into music, I felt nothing but support from my father. What’s more, a lot of the things he taught me carried over. For example, he showed me that art is not about competition. Although he was prolific, remarkably, he never compared himself to anyone else. He was humble, and for an artist of his calibre to be like that made a deep impression on me.

Photograph by Andy Stewart

Most of all, when I think of him as a photographer, I think it was his refuge. He’d go into the darkroom for hours, put on some classical music, and more often than not produce something wonderful. I think of him also as someone who did his art for it’s own sake. He didn’t make a red cent from his work until he got his grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities to document the Puerto Rican Diaspora. I was out here in California at the time, and I remember the phone conversation we had, where he said, Imagine writing a grant for yourself, for everything you do well, and for everything you want to do, and getting funded. This was 1979.

Identity is a deep thing

I never saw myself as Puerto Rican, or recognized that my father had been looked down on or mistreated because of the color of his skin. That was inconceivable to me, a boy who was loved by his father. Growing up, I didn’t know what he was involved in either. We were too young in the 60’s to understand much. It wasn’t until later that I began to piece together what he was doing, and to see how the past, and the events of that era shaped the man I knew.

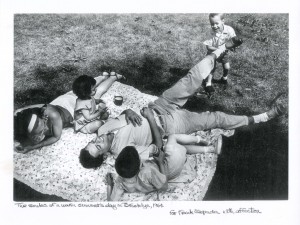

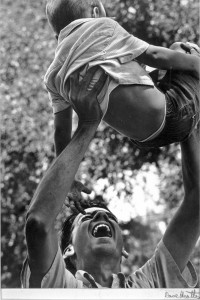

I have this image, of being so close to someone, that all you see is their eyes. This is how it was between my father and myself. I always felt close to him in a way that didn’t allow for me to see anything other than his love. You can see this in the photographs Dave Heath took of our family, one Summer’s day in 1964.

Photographs I and II by Dave Heath, III, unknown

I needed some distance, paradoxically, to understand the man my father was more fully.

When I started organizing his photographs, I had no idea that I would need to know where they were taken, or their context. I didn’t know I would need to be able to trace out a history of my father, in order to be able to describe what took him into different communities with his work, and with his camera. But this is what happened. Thankfully, I have my mother to ask questions, and gradually I began to be able to put together his remarkable history. I’ve realized, looking back, how I knew that person dearly, loved him and was loved by him, without knowing the events that made him. Now that I know more, it only adds to my esteem for him, and to the feeling of being blessed to be my father’s son.

I see now that I inherited some part of his clarity, his joy, his sense of humor, his creativity (just a small part, mind you), as well as his impatience, anger, and our family tendency to depression. I know I took to Buddhism and meditation on account of this feeling that this is what my family needs more of. We inter-are in this way, I’m sure of it.

I remember one time in the early 1990’s when my father was getting ready to give a lecture and slide presentation here in SF, and he was getting frustrated with the process of trying to select some slides. They were scattered across the big wooden dining room table, and he was about to give up. I told him, Da, when I look in the dictionary under the word ‘generosity’ your picture is there – so why don’t you just focus on that, and think of this event as a gift you can give these people? You know, most of them have never seen your best work, why don’t you just share some of it? I’m glad to say that worked that night, and I went with him to a well received event. It wasn’t unusual to have people ooh-ing and aah-ing throughout a slide show, and that gave my dad a lot of joy.

A Prayer for Martin Luther King, Daniel and Raphael, and Dona Pura

My father did his art whether or not it was going to be received. As I said, he did it for its own sake, and it kept him sane, most of the time. I got something of this dedication, stubbornness, and love of art from him. I also got some of his right values – compassion and caring for others, and his fearlessness and passion for social justice, for which I am eternally grateful.

When it came time to figure out what to do with his art, to be honest, I wouldn’t have trusted anyone else to handle it. For one thing, almost anyone other than a close family member would have mixed motivations for promoting his work. Another reason is that I learned his language from an early age, and I was lifted up by his art from the time I was in grade school. I remember laying on the floor of our house in Valley Stream, and looking through some books of photographs. I came across one that was all scenes at a racetrack, and went through it all, thinking it was very good before seeing that it was by my father. I realized then that he was right up there with all those other artists whose books we had. I’ve been his biggest fan for a very long time.

It seems that all this just sort of fell into my lap, and it was a good thing that I had the time to give to it. It took almost three years, nearly full time, and with the support and encouragement of dear friends, to accomplish the task of getting his Diaspora work into the National Museum. And so one chapter ends, and another begins.

Some gifts unfold over time. It’s certainly been this way with my father’s gifts to me and to others. I had no idea that what is given opens in this way. Now I know how it is. This joy continues.

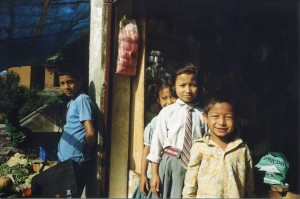

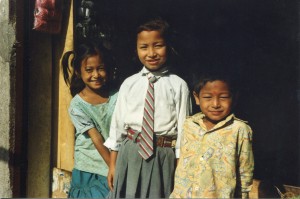

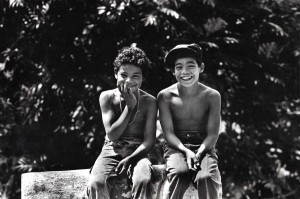

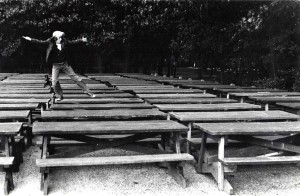

Jason dancing on the tables; Five kids on a country road, Puerto Rico, 1968

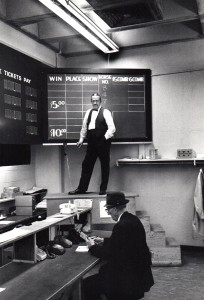

The Man with the Trumpet; NAACP Convention, Albany, New York, 1967

Da –

you may be surprised to know

how something of what you left behind

jumped up and shook me by the shoulders

how some of it pounded on doors until they opened,

how some of it told me what to say,

and how some of it continues now –

reviving the stricken,

answering our needs

just as it was when you are you were in your prime,

and as it will be

To see more of Frank Espada’s photography, visit thefrankespadagalleries.com

Wow, Jason, what a tribute to Frank. I’m honored that you included a photo of me and am glad that my suggestion had some relevance. Most of all I’m grateful for knowing Frank because he was a brilliant teacher and I learned so much from him….it wasn’t all about photography though. I learned to have faith in my own work and because he valued it, I came to value. It was one of his many gifts to me.

I met Frank when he responded to my notice posted on the Golden Gate Tennis Court’s board advertising for a partner, some time in the mid-fifties. Over the years, not only did we become fast tennis buddies but close friends as well. He and I and Marilyn and Michele had some great times together in SF and in Hawaii. Frank’s favorite line to me was, as we in our fifties still stood out there and played some genteel sort of tennis, that he missed that essential “second and a half,” when of course the athlete’s lament has to do with “split second.” A great guy.

Absolutely beautiful and highly inspiring. Thank you for honoring your dear dad, my dear friend and mentor, so lovingly and eloquently. As you are so acutley aware, he deserved as much and much more. His heart and dedication were such that his legacy will grow and his teachings will flourish exponentially, now largely due to your noble efforts and persistence in continuing the good fight and bringing his work to where it needed to be. abrazos . . .