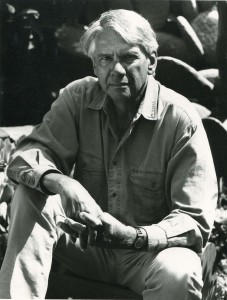

On 29th St., in San Francisco. Photo by Jason Espada

The following was written in 2014, in preparation for visits from curators, who were coming to view the entire range of my father’s work, within the space of a few short days. I took this as an opportunity to touch upon the most significant events in his life, and to celebrate the man I had come to know more fully through organizing his archive.

My purpose was two-fold: first, to introduce Frank Espada’s photography, produced over 60 years, by telling his life story. Second, I wanted to communicate something of what I have come to experience in working with his art. I feel now that each component complements the others, and that when the individual photographs are viewed in the larger context of his life and work, it is a richer and more powerful experience.

A sketch of Frank Espada’s life, set down by the main time periods, with a few details

Here are the subject headings, followed by a description.

1. Early life: 1930 to 1949

2. Marriage and the post-war years, New York, 1950 to 1960

3. Years of activism, New York, 1960 to 1973; and Washington, D.C., 1973 to 1979

Interlude: Becoming disillusioned with politics, and turning again to art

4. The Puerto Rican Diaspora Documentary Project, 1979 to 1985

5. Moving to San Francisco, the Y. E. S, and Chamorro Documentaries, and his years of teaching, 1985 to 2005

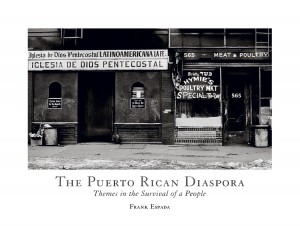

6. Publishing the book, The Puerto Rican Diaspora, in 2006, at the age of 76

and,

7. Later years, some late recognition, and his color work, 2006 to 2014

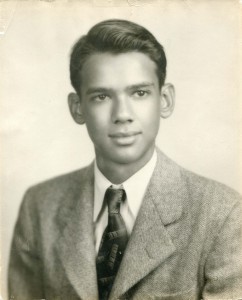

1. Early life: 1930 to 1949

My father was born in Utuado, Puerto Rico, on December 21st, 1930. From what I understand, his family there had some social position – his grandfather, Buenaventura Roig, was mayor of the town, and his father was successful enough to own property and support other family members. Some events transpired that made it so that Frank’s father needed to leave the island. He went to New York to look for work, and after a time sent for his wife, my grandmother, and their two children, Frank, and his sister, Luisa.

Frank with his mother, 1931; Frank with his sister and mother, 1939

They crossed from Puerto Rico by boat, went back the island, and then came back again to New York. The story goes that the boat they came over on, the San Jacinto, was torpedoed on its return crossing by German U-boats.

We have a few family stories that have been passed down. One is of my father seeing his father cry at night because he couldn’t get a job to support his family. The signs said “No Puerto Ricans need apply”. The other story is of my dad being taken to his first baseball game in New York and seeing no black or brown skinned players on the field. He had grown up watching great ball players in Puerto Rico, including members of the Negro League who would come to the Island in the Winter to play.

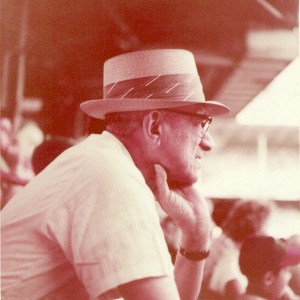

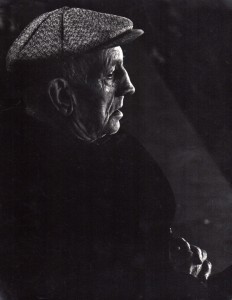

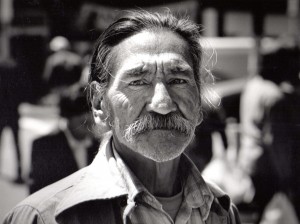

Frank’s father, my grandfather, Francisco Xavier Espada, at Ebbets Field, Brooklyn, New York, 1956.

My brother also writes about my father working carrying ice up flights of steps in the 1940’s. See “The Immigrant Ice boy’s Bolero”, my brother’s first book of poetry.

I remember one family story of my father as a young boy standing up to a bully. The story goes that Frank was being regularly terrorized by a neighborhood bully, and that one day he decided he’d had enough. The next time he saw the boy coming at him, my father picked up a huge rock and the other kid turned and ran and never bothered him again. The next day, the story goes, my father went back to that same spot, and couldn’t even lift that rock.

This story was always part of what was behind what I remember my dad telling us as we were getting ready for school in New York in the 60’s – he’d say “Don’t take any shit from anybody”. You could say we had standing up to bullies bred into our DNA. I know that the images told me we have strength we only seldom know about, but that will be there when we need it, so we shouldn’t fear, especially in the face of some oppressor.

The last weekend of my father’s life, we talked about how as a young man he made his way into the City College of New York, which was considered a top notch school. He told me that he remembered reading the plays of Plato, among other things and said he knew he had found a home in the Humanities. I asked him how many people of color there were in his classes, and he said the ratio was about 1 to 200 white people. He said he was told by more than one instructor there that he shouldn’t waste their time, essentially that he wasn’t good enough to be there. That he proved them wrong in the end is bittersweet. He was awarded an honorary degree by Lehman College, CUNY, in 2008.

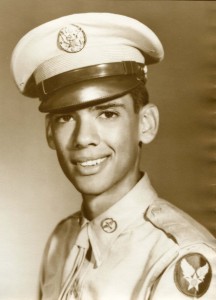

In my mind I round out this part of his life with him not being able to afford books, being discouraged by his teachers, and, with his parents divorcing, him joining the Air Force in 1949, something he regretted for his entire life afterwards.

On leave from basic training in Texas, during the Christmas break 1949, on a bus on the way to New York to spend the holidays with his family, he was arrested in Mississippi for not moving to the back of the bus. My brother tells this story well. When he went in front of the judge, the judge asked him how long he had on his furlough, and he answered that he had one week off, whereon the judge sentenced him to one week in jail. As my father told it, that was the best week of his life because in that week he decided what he was going to do with the rest of his life.

Many people who go on to become activists in one form or another have one incident that galvanized things for them, and certainly there were other events that were to bring out the radical in my dad, but this stands out among them.

I’ve often thought how close my father came to losing his life back then. In the 40’s in the South, people of color “disappeared” all the time, and no one was held accountable. He must have known this when he was refusing to move to the back of an empty bus late at night, but at some point, anger and dignity rise up in a person, and, even if it were to cost them their life, they make their stand. There were no witnesses, but, for me, that event resonates to this day.

2. Marriage and the post-war years, New York, 1950 to 1960

Frank met Marilyn in 1951, and they married in 1952. My mother has some interesting stories to tell of how she viewed my dad, how her family viewed him, and all non-Jews back then for that matter, and how she came to know something of the anger at being discriminated against that he carried with him. My mother also tells of their being Dodger fans, and particularly fans of Jackie Robinson, and his significance at that time.

Wedding day, January 26th, 1952. From left to right: Frank’s maternal grandmother, and mother, Frank and Marilyn, Marilyn’s mother, Jeannette Levine, and Frank’s father.

Wedding day, January 26th, 1952. From left to right: Frank’s maternal grandmother, and mother, Frank and Marilyn, Marilyn’s mother, Jeannette Levine, and Frank’s father.

After a second stint in the military, my father went to the New York Institute of Photography on the G.I. Bill. He also met the to-be renowned photographer Dave Heath, who he regarded as a mentor and friend. Dave introduced him and a small group of like minded photographers to Gene Smith, and they studied with him in the late 1950’s in New York.

.

At the New York Institute of Photography, 1954

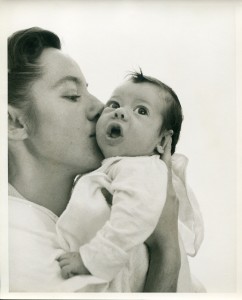

‘Kissing the baby’ – Ma and Martin

‘Kissing the baby’ – Ma and Martin

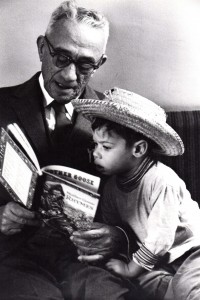

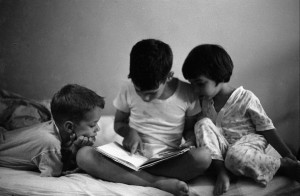

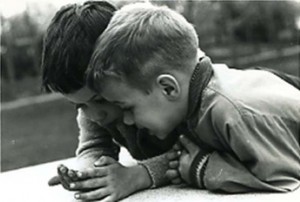

My brother, Martin, was born in 1957, I followed in 1960, and my sister came along in 1961. Looking at the photographs my father took in those years, I have the sense that he was developing what I call “his loving eye”. My mother says they were all scenes of affection that he was photographing, and we can see this is true. Looking at them now, I see in the pictures how he looked at us, with joy himself, and with the warmth and love he felt for each of us.

Grandpa reading to Martin, Martin reading to the two of us, and Lisa being held by grandpa

My mother tells a story of being woken up at 2 am one night by Dave Heath and my father, who had been out drinking, and Dave insisting that my father quit his job and become a photographer full time. My mother can tell you exactly what she said, but the gist of it was, “can photography pay the bills? We have three small children, and if the answer is no, then forget it” – or something to that effect…

My father worked as an electrical contractor for a company called T. F. Jackson from 1955 to 1965, of which my dad would say bitterly were “The best years of my life”, regarding that time in some ways as a complete waste. I would later tell him the sense of it I had was that it was a thrust block for him, as an artist, and an activist, and that when the way opened for him to use his talents in creative and constructive ways, he took to it with a real power that came from knowing how soul deadening it is to work for a paycheck alone.

Back then, my father would send us to bed at 7:30, whether it was dark out or not, and cover the windows with frames covered in black fabric that he had made. He would then print on the kitchen table, “with a $29 dollar enlarger, including the lens”. One photograph he made, of my mother, is on our wall now. Ma remembers that it was taken in 1961, shortly after the birth of my sister. When she saw it, she said, ‘But oh, look at my hair’, and my father said, ‘Never mind. Some day you will love it.’ And he was right. Here is that photograph:

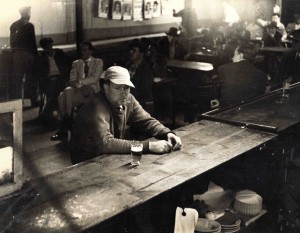

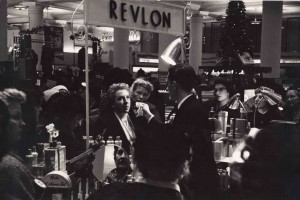

During these years you can see my father’s artistic and humanist qualities in the photographs he took at Fountain House, a half-way house in New York, and in his Racetrack series, from 1958, and 1959, respectively.

Fountain House

Racetrack

From the earliest days in his photography, my father’s composition and printing skills were simply there. All that remained to be developed, from what I could see, was his personal, signature quality that I recognize now in all of his work from the early 1960’s on.

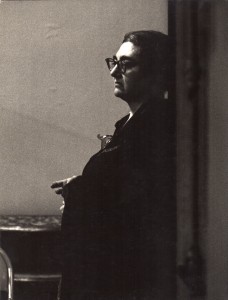

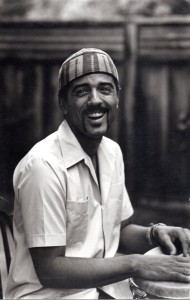

In his photographs from the 50’s, it’s quite likely the people had no idea that he was taking their picture. From the early 60’s, though, and on through the rest of his life and career, another quality enters into it, one I associate most of all with my dad’s work. In almost every photograph of people, he is engaging them, often in conversation before and during taking their picture.

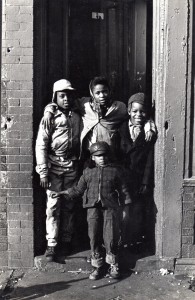

Kids in the doorway, Tito, Cindy

One friend referred to an intimacy that can be seen. My father knew how to make people feel respected, and cared for, and they relaxed with him. So, even though my father didn’t talk about himself much in later years, or about what made his photographs special, those who knew him can look at his images and say, as one did recently, that “they are full of Frank’s heart”.

Lisa at four, me and my brother

3. Years of activism, New York, 1960 to 1973, and Washington D.C., 1973 to 1979

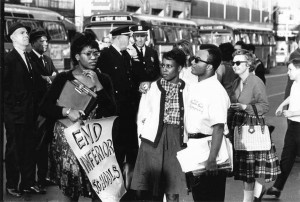

The racism in this country, in particular before the landmark civil rights legislation of the 60’s, was pervasive, and something that needed to be fought against at every turn.

We were approached recently by someone who has taken on the task of documenting the role of Brooklyn CORE (Congress of Racial Equality), and highlighting what he sees as this organization’s central position in the achievements of that period. My own sense of how things unfolded back then, however, was that what took place during the civil rights era was very much a de-centralized movement, with many local, grass-roots organizations cooperating and gaining power and legitimacy, but most of all achieving greater and greater results for minorities.

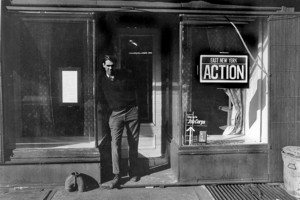

My father had an important role in this time, as a natural organizer. Many people cite him as a trailblazer, and mentor. He founded East New York Action, on Blake Avenue, ten blocks from where we lived when I was born.

As I’ve heard the stories about what they set out to do, I have the vivid sense of what it means for something to develop organically out of the needs of a community. East New York Action organized rent strikes, educated people on welfare rights, and registered voters, among other things.

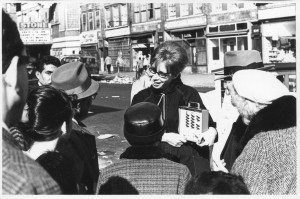

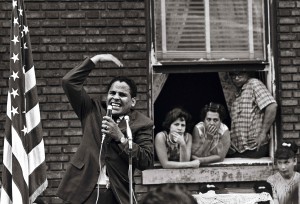

Voter registration / voting machine demonstration, East New York, 1964.

In her book on welfare rights in this country, Felicia Kornbluth cited East New York Action being one of the first organizations to develop the tactic of rent strikes as a political tool.

As important as all this was back then was the fact that groups worked with other neighborhood organizations. Witness my father’s association with Evelina Antonetty, at the United Bronx Parents, Cesar Perales, and others who cite him as a leader and inspiration. Such was the activism of the time.

In 1965, Manny Diaz gave my father his first paying job as a community organizer, with the Puerto Rican Community Development Project. They would remain lifelong friends and allies.

Evelina, Manny Diaz

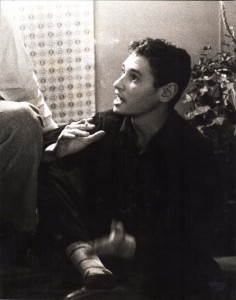

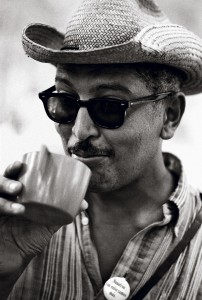

I’ve told his San Francisco students who knew my dad when he was in his 50’s and 60’s that they got the more mellow version of my father. That got a laugh. They knew him when he was a lion, but back when he was younger, in New York and in his 30’s and 40’s he was a dragon – a really imposing figure. It didn’t hurt that he looked like a movie star, a claim we can back up with pictures, and that he had a booming voice when he wanted to. He was both brilliant and charismatic. As one person who encountered him back then put it, his presence filled the room.

With Richard Cloward, a leading figure in the welfare reform movement, circa 1965.

Two things that came out during the East Coast memorial for my father, concerning those years: how he was respected by black leaders in New York, and that in the early 1970’s he was the first to arrange meetings between Puerto Rican and Mexican activists.

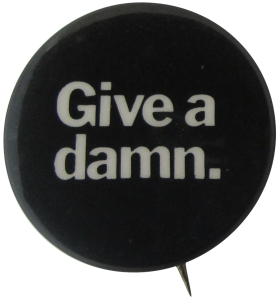

Like many other important figures of that time, my father was part of many groups, often simultaneously: he was the founder of East New York Action, a Vice President of The New York Urban Coalition. (I remember wearing a “Give a damn” button to school back then – their ad said, “Give a damn about your fellow man”). He was also a Deputy Commissioner of The Community Development Agency of New York City.

The Drug Abuse Council

My earliest recollection of telling friends what my father did was to say he represented minorities on a Nationwide level in the drug abuse field. I had no idea what I was saying, beyond that, or what it meant at the time. I later learned that in the 1960’s, corporations were being approached for funding for drug treatment programs, and that they quickly realized they didn’t know who was a legitimate advocate, or where their resources would be best used. For that reason the Ford Foundation and others founded The Drug Abuse Council, that had Fellowships for advisors. In its second year, I believe, my father was a Fellow, and it was this work that took us in 1973 to the Washington D.C. area.

In all this time, my father did not earn his living with photography. He was an organizer, and, as I remember one person telling me, he always had his camera with him. We have images, then, of East New York in the 60’s, rent strikes, the famous school boycott of 1964, the March on Washington, the Young Lords, and Lincoln Hospital’s drug treatment program in the 70’s where acupuncture was used to help people who were dealing with addiction.

Interlude: Becoming disillusioned with politics, and turning again to art

My father had a life-long disdain for politicians, bureaucrats and hustlers of all kinds. I can hear his already clear sense of disagreement with his activist colleagues in an interview in 1980 with the future Secretary of New York State Cesar Perales. In it Frank asks him about the legitimacy of appointed representatives, who would supposedly advocate for minority rights, but who had no grassroots, or community level recognition or support. Cesar answered that there was a place for such people who, “knew how the system worked” and could get things done. Clearly this is so, but you can imagine this situation at its worst as well, where professional politicians moved in and took over the process. I think this is what my dad saw happening more and more to minority representation in the late 60’s and early 70’s.

Others, such as the family friend Willie Vazquez can tell this chapter better than I, but, as I understand it, my dad gradually moved away from what he saw as the corruption of democracy and the disenfranchisement again of the underclass in this country.

4. The Puerto Rican Diaspora Documentary Project, 1979 to 1985

The Man with the flag, Washington D.C., 1981

By the time my father got funding to work exclusively as a photographer, his art was already fully developed. His political philosophy as well was completely developed, from almost two decades of activism. Receiving a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities in 1979 then, gave Frank the opportunity to realize the long held aims that he had for both his art and activism. I remember the phone conversation we had where he said to me, “Imagine writing a proposal for everything you do well, and for everything you want to do, and getting funded for it.” The Puerto Rican Diaspora Documentary Project took him across the Continental United States, to Hawaii and to Puerto Rico. He conducted over 140 interviews, in some cases with people he had known for decades, but mostly with people who came to know him as an advocate.

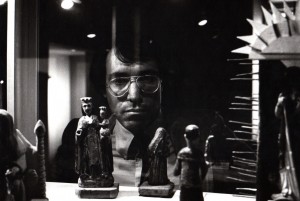

Confessor Rivera, Kona, Hawaii, 1981; Jack Agueros, with the Santos de Palo Exhibit, at El Museo del Barrio, New York, 1979.

There has not been a project before or since of the range and quality of my father’s project documenting the Puerto Rican experience in the 20th century. Nothing even comes close. The project culminated with 45 exhibitions over a ten year period, brought to local galleries in the second phase of the project by Padrino, or patron, organizations. Twenty years after the exhibitions, a book would be produced with photographs and framing accompanying text.

For me, the book is passionate, infuriating, depressing, uplifting and beautiful all at once. It represents what art can be in the hands of someone committed to social activism, in other words, a full human being. This is a work that awakens the best in us all.

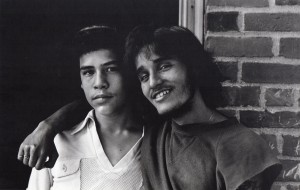

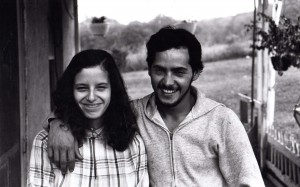

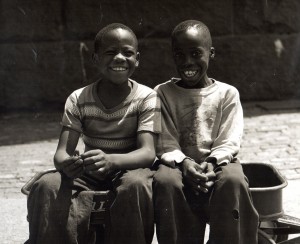

El Ministero, New York, 1963; Angel and friend, Hartford, Ct., Christina, Barrio Tokio, Puerto Rico; Manuel and Sandra Molina, Kennet Square, Pa.

As of this time (August, 2016), the oral history interviews from this project, “Voices from the Puerto Rican Diaspora”, have yet to be transcribed, translated, and published.

5. Moving to San Francisco, the Y. E. S, and Chamorro Documentaries, and his years of teaching, 1985 to 2005

Michael Lesser at the UC Berkeley Extension gave my father his first opportunity to teach, and right away word began to spread of this extraordinary teacher. Reading the testimonials, even from his fellow teachers, they all say that my father offered something that few, if any other teachers had to give. Technical expertise aside, by that point in my father’s life, he could easily focus on the aesthetic and social vision that could be accomplished with photography. Many students asked for private lessons, and so began the famous workshops my father offered from their home.

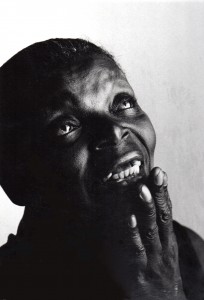

Community Health Outreach Worker, San Francisco, 1990

From 1989 to 1991, my father also worked for Y.E.S., or Youth Environment Studies, founded by Harvey Feldman. In those years, Frank documented their landmark efforts to combat the spread of HIV and AIDS in San Francisco among the underclass of IV drug users. The aim of Y.E.S., according to Jerry Mandel, was to address all of the problems associated with drug use from a sociological perspective. Frank’s connection with both Jerry and Harvey went back to the Drug Abuse Council, where they were all Fellows in the early 1970’s.

Y.E.S had a national reputation because of Harvey Feldman’s long involvement in the field of policy and drug treatment, so when the AIDS crisis hit in the 1980’s Harvey recognized that a second wave would be coming that would effect IV drug users in particular. His organization started the then unheard of method of handing out first bleach, and then needles, as well as condoms, and encouraging life-saving changes in people’s regular drug using behavior. As Jerry put it, AIDS went in that time from being a death sentence, to a life sentence. Y.E.S. also developed the concept of the compassionate Community Health Outreach Worker (or C.H.O.W.) who could engage an at-risk population. Their model programs went on to be replicated on a nationwide level. This is what my father documented in those years, and his powerful images were used for education and fundraising purposes.

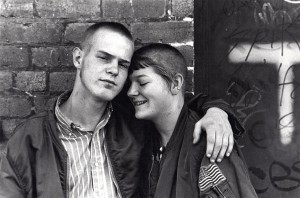

Shirley Green Tenderloin couple

At 16th and Mission

Holding hands

The Chamorro Documentary Project

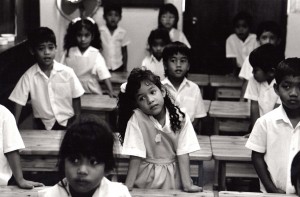

In 1990, Frank was asked by his friend and colleague from Chicago, Samuel Betances, to photograph the Chamorro people of Guam, Saipan, Titian and Rota in the Marianas Islands. Modeled on my father’s Puerto Rican Diaspora documentary, their aim was to chronicle the culture, as well as the social challenges faced by this group.

Segundo Blas, woodcarver, keeper of legends, Mangilao, Guam, 1990

My father’s teaching continued in the 90’s at the Berkeley Extension, and the Academy of Art College, and he encouraged and helped to develop the careers of a number of magnificent photographers, including Ken Oppram and Karen Ande.

After decades of living with potential that was yet to be realized, my father had an instinct for his students’ artistic and personal vision and he was fully committed to helping them each fulfill their aims, and to go beyond what they thought was possible. He delighted in teaching, as it brought together his art, political conscience, gift for communicating and love of people.

When I would pick him up at school after class, or would stop by my parents’ home when there was a workshop going on, I would smile because I knew his students were getting something very special.

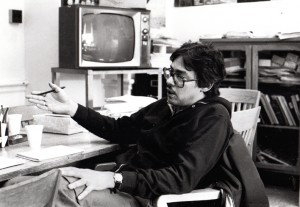

A workshop on Teresita Blvd

At his memorial here on the West Coast, many former students came, decades after they had studied with him, and all of them spoke of how his influence has remained with them, guiding and encouraging them over the years. It has been a great comfort to my mother, sister and to myself to hear this.

6. Publishing the book, The Puerto Rican Diaspora, 2006, at the age of 76

When lifelong friend Julio Rodriguez called my father on New Year’s Day, 2006, and told him “It’s time to get your book published” he thought he was kidding. It turned out he was serious, and he made the offer that day to support making that dream a reality. There had been a few false starts with proposals to have the book done. Most of the time my father wasn’t satisfied that it would be to his standards, and his feeling was he’d rather not do it, if it couldn’t be done right. Over the course of the year working with the book designer, Doug Da Silva, my father was re-invigorated. He was viewing again images taken in some cases more than 40 years before, but many of the stories he remembered as if they had just happened.

When I was in the process of cataloguing his darkroom work, I noticed that the name of the person photographed was often on the back of the print. My father not only remembered their names, but their stories as well, and this brought up a lot of memories and emotion for him. An artist has a lot to deal with, and the real work, from what I’ve seen in my father’s case especially, is being that sensitive and feeling so fully and also keeping one’s balance. We all did what we could to help, but on a number of levels, exhilarating as it was, we can also say it was not at all easy on any of us. I’m glad he did it, of course, more than I can say, but what an effort it took!

7. Later years, some late recognition, and his color work, 2006 to 2014

In 2008, Frank Espada was awarded an honorary degree from Lehman College, in New York, and this was something he was proud to receive. Many of his long time friends, such as Willie Vazquez and Julio Rodriguez turned out for the event.

At Lehman College. From left to right, standing: Olaf Ringdahl, Abdin Naboa, (unknown), Ish Betancourt, Pancho Cintron, Filipe Floresca, Luis Garden Acosta, Gladys Pena; seated: Willie Vasquez, Marilyn and Frank, Julio Rodriguez.

The Library of Congress purchased 75 of my father’s prints in 2009, and in 2010, Duke University acquired many of Frank’s papers, teaching materials, and a good number of his documentary photographs. Their aim is to continue to use this material in their Documentary Studies Department, as well as in their courses on History and Human Rights.

We can add now to this list of accomplishments, the acquisition of the Puerto Rican Diaspora Documentary Project by the Smithsonian American History Museum in 2016, their American Art Museum, and the National Portrait Gallery having also acquired a select number of his prints.

John Santos, and Juan Gonzalez, at the National Portrait Gallery

Two boys in a wagon; Alberto, at the Smithsonian American Art Museum

In his last years, my father turned to color photography, making beautiful digital prints of the sky and ocean from his home studio. I took his move to color as his needing another photographic challenge to surmount, technically, which, astonishingly, he succeeded in with each new mode of printing.

I also take the art of his later years as absolutely being on a continuum with all that came before. In it, he is focusing on what is positive, always new, tangible, and all of our common heritage. He was always the humanist, and a day didn’t go by when he wasn’t aware of both the beauty and the injustice in our world. He lived his life as the most eloquent and persuasive answer to those facts.

In his latter years, my father had a number of health problems that limited his mobility. Fortunately, they had an amazing, ever changing view from their balcony in Pacifica, and all of my father’s Pacific Skies images were taken from the same vantage point, although, owing to their diversity you would probably never guess. My mother heard me telling someone that when Frank Espada couldn’t go out to beauty, beauty came to Frank.

My father also had trouble hearing others, even with high tech hearing aids, and I know this was isolating for him, and yet he persevered taking beautiful images until the last weekend of his life.

I like to think that in his later work, my father is looking into the face of eternity and eternity is smiling back. Of all his photographs, some of these of the sky, the light, and ocean are the ones I choose to have around me in my room. They are uplifting every time of day and night, which is as my father intended, his last gifts from his great heart to us all.

Quiet light

To see more of Frank Espada’s photography, visit thefrankespadagalleries.com

For a comprehensive collection of resources on the Frank Espada Archive, including audio and video interviews, visit

I’m a second cousin of Frank, I have been thrilled by your narrative of your father’s professional endeavors and his artistic seal. I had various moments in my life to be with him, when he brought his exhibition to Puerto Rico. I’m very proud of your father and remember him dearly. My best regards your mother, brother and sister. José M. Morales Espada

I enjoyed reading your memories of your father Jason!!!

I was your father’s best man when he married your mom.

They had 58 years of marriage

Obviously he was the best man.

I am proud to have known him.